Both exhibits are created by self-styled master of plastination (and living reincarnation of Rembrandt’s Dr Tulp), Dr Gunther von Hagens.

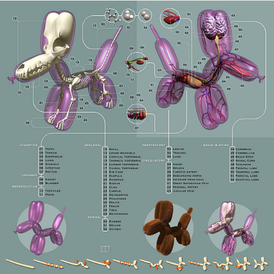

Put simply, plastination is a preservation method that involves replacing the water and fatty tissues of a ‘specimen’ (animal or human) with polymers. This preserves the specimen and prevents decay and smells (a more in-depth explanation is available on the Body Worlds website).

The process allows von Hagens’ teams to create and exhibit things that would otherwise never be possible – Animals Inside Out features an elephant stripped of his skin and a hare made up only of capillaries among the displays.

Animals Inside Out is fascinating, and I would recommend it to anyone, but what surprised me most about it was my reaction to some of the displays – and how that differed from my reaction to Body Worlds.

In Body Worlds, you entered and were immediately faced with the corpses (if you can call them that; more on that in a moment). At the Natural History Museum, there is more of a feeling of build up throughout the exhibition.

The first displays are plastinated, but whole and intact, squids and cuttlefish. These are followed by skeletons and then more unusual exhibits: a horse’s head displayed in cross-section; a skinned bull and so on until the final room which features several large mammals whose anatomy you can study. It is one of the best-curated exhibitions I remember seeing in a long time: the rooms are perfectly laid out in terms of spacing and information and the flow works well, so that you are drawn through, gradually learning more and seeing more and more impressive things.

But I wasn’t prepared for it to make me feel slightly ill. Despite the name, I don’t consider myself hugely squeamish: I grew up helping out on a farm with things like birthing calves; and despite the fact that I haven’t eaten meat in two decades I could tell you how to skin a rabbit or pluck a pheasant. The only thing that bothers me about meat is the smell.

Now, it’s not as if I had to leave the museum because I was grossed out, but I did find that I couldn’t bring myself to eat anything for several hours after my visit because every time I tried I felt queasy. What was going on? And why hadn’t I felt like this after seeing the human exhibits at Body Worlds?

In this interview anthropologist and taxidermy researcher Jane Desmond argues that the way in which the bodies are presented transforms them into scientific specimens:

“both by von Hagens' special "plastination" drying process and through the removal of the skin (and with it markers of age, fitness, social class, racialized status and so on). This distance allows us to approach the exhibit in a "learning" mode, a stance promoted by the design of the exhibit, which invokes the history of anatomy and science in the service of understanding health and illness.”

“…the plastination process, which makes the displays possible, simultaneously banishes the pliability of our bodies, their smells and their viscosity. The bodies, as "specimens" in the exhibits are dry, have no fluids, no fats, no smells, no movement, and no real eyes (artificial eyes are inserted into the faces). The "livingness" of these bodies is long gone, and as such as I looked at the exhibit I found myself mostly unaware of being surrounded by the dead or by death.”

For me, this process didn’t work in the same way with the plastinated animals. Most of us are unused to seeing human bodies – but animal carcasses hang in butchers and can be seen every day. Faced with a bull stripped to show muscle, my brain helpfully supplied the sensations I associate with such a sight, including the smell of blood and feeling of nausea.

A human body presented as a scientific exhibit is unusual enough that we react to it in that way. Animals, on the other hand, are more commonly used in a variety of ways – as meat; art; adornment and study. I had a whole host of other cues and memories to respond to here.

I opted out of the frog and rat dissections that were an optional part of my Biology A Level, but I would rather see animals used in an exhibition like this than reared in horrific conditions and then slaughtered for cheap protein by a society that has many other options available to it. I may have reacted in an unexpected way to the exhibitions, but what I took away will last for longer – the things I learnt from it. Horses cannot vomit; elephants have large hollow areas within them to ensure they can support their own weight and wade through deep water without the pressure crushing their lungs. The knowledge of how a rabbit’s muscles fit together and give it the power to jump; the sight of a giraffe’s oesophagus, longer than my leg.

These, and more, are why I would go again to this exhibition, no matter what accompaniment my subconscious might decide to supply. There is a lot to be learned from seeing our fellow creatures in a new way – I imagine anyone interested in anatomy would learn more from these rooms than any textbook.

Squeamish Louise

RSS Feed

RSS Feed